The Renaissance, according to Professor Stuart M. McManus, happened almost everywhere.

Professor McManus, a lively historian from the Department of History at The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), sees the Renaissance as more than just a European affair – it was a global party, with cultural fireworks lighting up the skies across continents. His fascination with the Renaissance extends beyond the traditional European narrative, viewing it as to some extent a worldview phenomenon that touched large parts of the world.

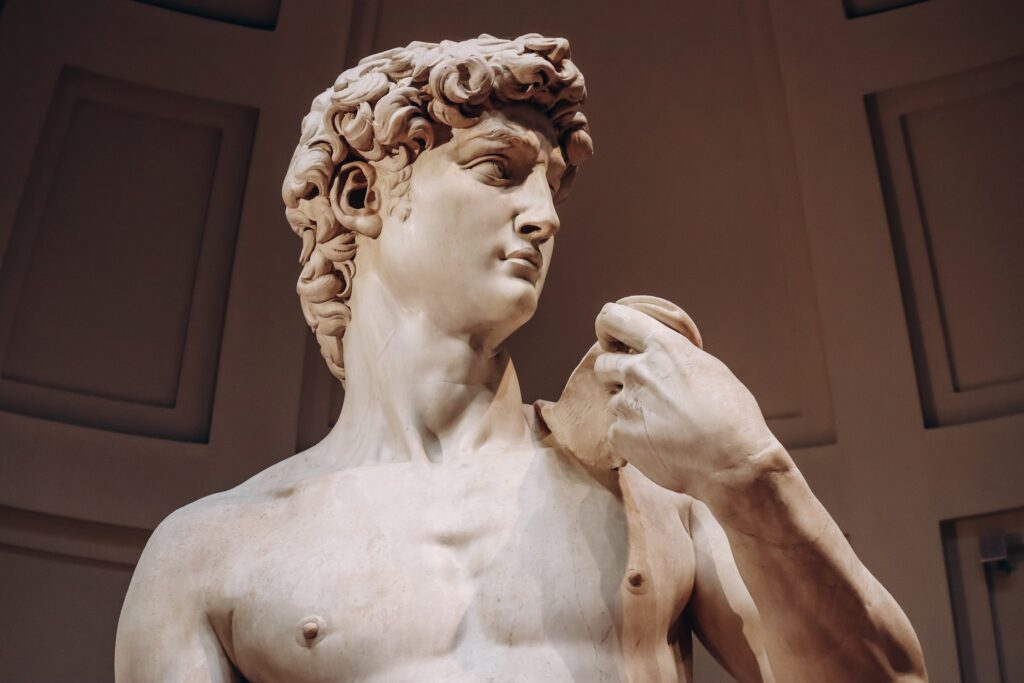

His journey began at the age of 12 or 13 when picked up a translation of Dante’s Inferno from a bookshelf at home. While studying European languages at university, he became enamoured of Florence, which drew him further into the world of the late Middle Ages and Renaissance. In addition to mastering various western European languages, he has since also dedicated himself to learning several Asian languages and writing thousands of pages on the history of the period 1400-1800 CE.

“I remain fascinated by the Italian Renaissance and what I call the ‘global Renaissance’, the unprecedented acceleration in the contacts between the cultures and humanistic traditions of the world that took place in the middle centuries of the last millennium,” says Professor McManus. “Many people talk about the ‘early modern period’ or think of history in terms of dynasties. It is also conventional to think in terms of the histories of peoples, nations and other groupings based on language, geography or other criteria. But this focus on the part tends to blind us to the history of the whole.

“Can you understand the market by looking at the performance of a single stock? No – you have to look at the performance of the market as a whole, which in turn usually tells you something interesting about your individual stock.”

“I use the term ‘global Renaissance’ to describe my work rather than ‘early modern global history’, ‘the history of proto-globalisation’, ‘Silk Road history’ etc. because I am interested in the sort of cultural flourishing that we traditionally associate with somewhere like Renaissance Italy, and I think the word ‘Renaissance’ is an evocative way to capture this.”

His work bridges parts of the world that are usually studied separately, such as the Americas, West Africa, and South China, shedding light on the interconnectedness of historical developments across continents. His first book, Empire of Eloquence – the Classical Rhetorical Tradition in Colonial Latin America and the Iberian World, published by Cambridge University Press in 2021, delved into a pivotal facet of Italian renaissance culture: the art of eloquent public speaking inspired by the styles of legendary ancient Greek and Roman orators like Demosthenes and Cicero. This focus on rhetoric formed the cornerstone of Renaissance education, retaining a prominent position in academic curricula as part of the broader field of the “liberal arts”.

During his research for the book, Professor McManus found the tradition extended far beyond the confines of southern and northern Europe. It had taken root in unexpected corners of the globe like Mexico City and Lima in Peru, as well as Christian outposts in Asia like Goa and the Philippines. He says: “It also influenced the sermons of contemporaries of Matteo Ricci in Ming China and elsewhere. The conventions of public speaking inherited from the ancient Mediterranean world mixed with other rhetorical traditions in interesting and unexpected ways. Ricci even taught the memory techniques of ancient Mediterranean orators to aspiring scholar-officials studying for the Ming civil service examination.”

Professor McManus describes his work on the global Renaissance as “finding the full extent of a tradition and its interactions with analogous and connected traditions”. Beyond its expansive geographical scope, his research also takes in a diverse array of subjects, ranging from language, law, religion to technology and more. This broad perspective encompasses both the positive aspects of the cultural movement, such as the spread of humanism, and its darker facets, notably the spread of slavery. His recent article, entitled Multiethnic Slavery and The African Diaspora in Macau: the Search for the Geographic Limits of Vast Early America, is the springboard for his next book, under contract with Harvard University Press, which will treat the history of slavery.

Beginning with the arrival of the first African slaves in British North America (Virginia, 1619), Professor McManus traces the global dimensions of the slave trade during this era. “I then go out from that moment to show how trading in human beings was common across multiple parts of the world in this period, with enslaved Africans even appearing in Macau and Guangdong,” he says. This darker side of the Renaissance period is important to highlight, even as we might more naturally be drawn to the more appealing elements of the period: the trade in silk or the first translations of the Confucian Four Books. “Law too is central to this story, because it was the prism through which learned people throughout the world tended to think about the slave trade, drawing on their particular inherited legal traditions,” he adds.

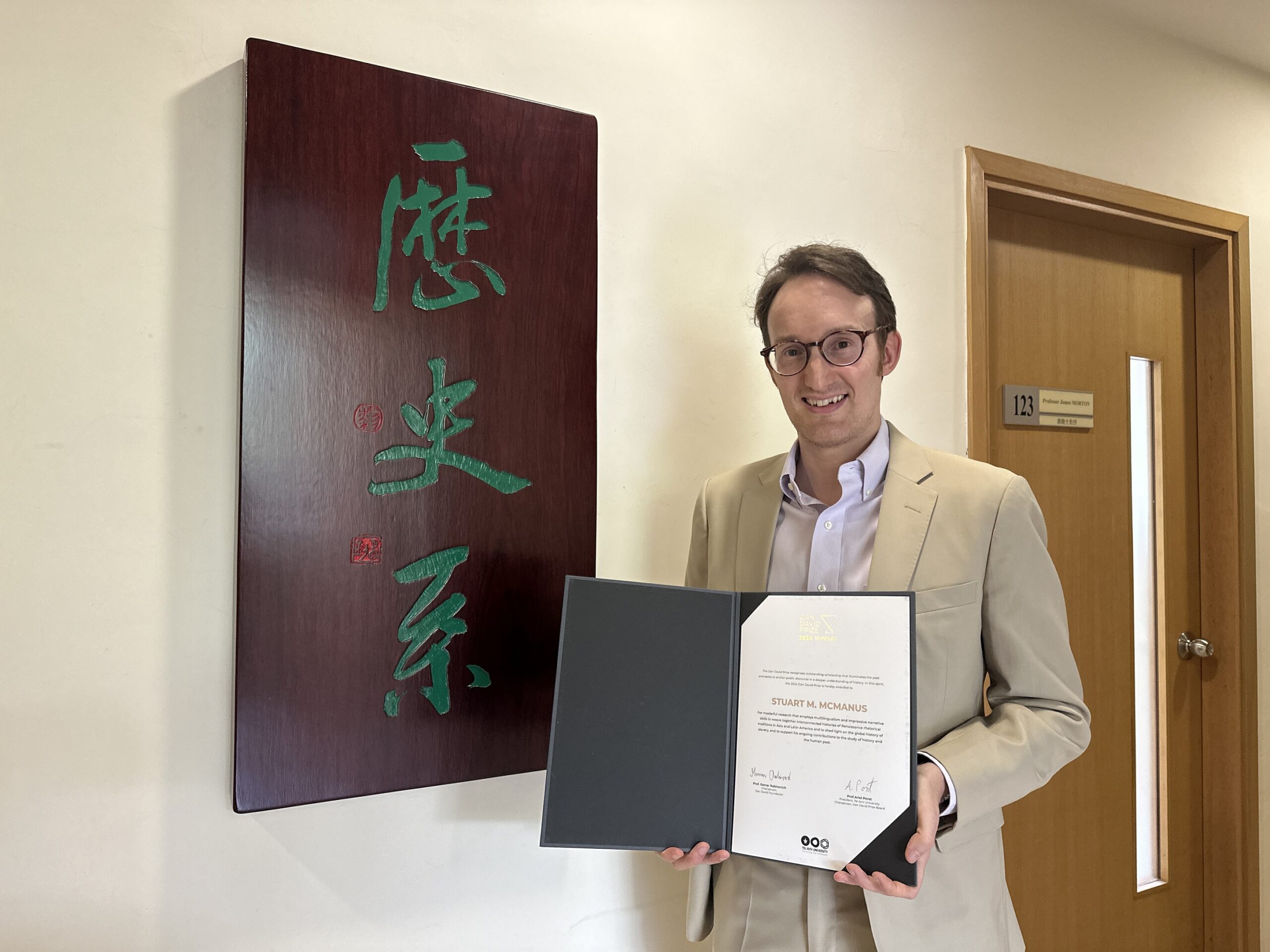

For connecting such a wide range of dots in our understanding of the Renaissance, Professor McManus recently became the first Asia-based winner of the Dan David Prize, the largest history award in the world, worth US$300,000.

His commitment to innovation has also turned him into a pioneer when it comes to using technology to illuminate his subject. He is in charge of a project to integrate data science into the Faculty of Arts curriculum. He also runs a lab focused on what he calls “cross-cultural analytics,” using machine learning to trace Chinese cultural influence in Renaissance Europe.

“It focuses on gleaning insights from the vast amount of data in multiple languages produced by humanity over its recorded history,” he says. “Because of CUHK’s and Hong Kong’s unique position in the world, I believe we are ideally situated to develop this field.”