They surround you, they live off you, they are a source of irritation, even a cause of danger and yet you never even see them. Astigmatic mites, the largest and most varied grouping of mites, have long been known as the major cause of human allergies.

Recently, a ground-breaking study led by The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK)’s Faculty of Medicine (CU Medicine) with researchers from universities in Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Wuxi, Macao, Thailand, South Korea and Singapore, has revealed their divergent evolution. The findings lay the genomics groundwork for diagnosis of and intervention in mite allergy.

Mite allergy could be a danger

Allergic diseases are immune-system disorders characterised by IgE-mediated immunological reactions, including asthma, allergic rhinitis and atopic dermatitis. They are especially prevalent and dangerous among children causing, for example, severe asthmatic exacerbation which can lead to death. The population-based International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) determined that about one tenth of secondary schoolchildren have asthma and 15% have atopic dermatitis. About one third of Hong Kong children aged 6 to 7 suffer from allergic rhinitis. In Hong Kong, house dust mites are the predominant triggers in about 40% to 60% of allergic individuals.

“Common symptoms of mite allergy include nose itching, sneezing, nasal congestion and a cough that is worse at night. In patients who ingested mite-contaminated food, severe symptoms such as shortness of breath, swelling of the throat, dizziness or even fatal anaphylaxis can also occur,” explains Dr Agnes Leung Sze Yin, Assistant Professor of CU Medicine’s Department of Paediatrics.

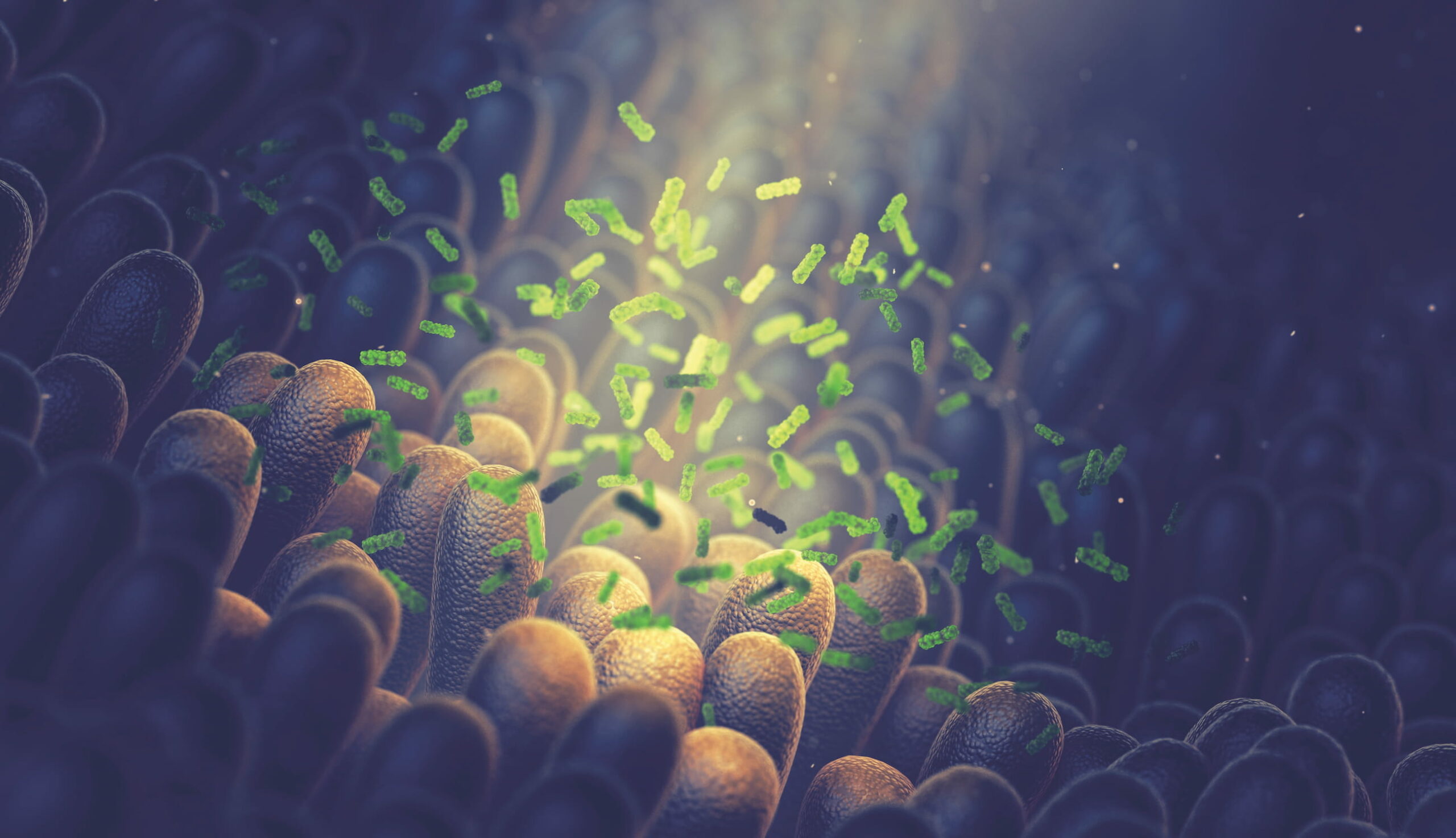

Astigmatic mites include house dust mites, storage mites and parasitic mites, or itch mites. The two free-living domestic species, house dust mites and storage mites, are major causes of human allergies. Dr Leung says, “Storage mites can exist in improperly stored food powders, while house dust mites can exist in household mattresses and soft toys, and scabies caused by itch mites can spread rapidly in crowded environments.”

An example she gives is of a 17-year-old girl who developed breathing difficulties, rashes and other allergic symptoms on the way to school and was diagnosed with anaphylactic shock. It was caused by consumption of pancakes made with storage mites-infested pancake mix that had been left open for too long in a humid environment, to which the girl had an allergic reaction. “Effective methods must be found to control these mites and minimise their effects on allergic individuals,” emphasises Dr Leung.

Uncover the evolutions of dust mites by genomic evidence

“Some of my old colleagues have had mite allergies, they couldn’t sleep well because of the red irritated skin caused by allergies. That’s the time I realised that many people are suffering from the pain and annoyance caused by mites,” says Professor Stephen Tsui Kwok-wing, Professor of CU Medicine’s School of Biomedical Sciences. With this in mind, Professor Tsui has been working diligently on mite genomics for over a decade and has led the research team that has revealed the comparative genomics of astigmatic mites using six high-quality genomes and cracking their evolutionary history, from emergence to extreme diversification.

Mites and ticks were formerly considered as a monophyletic group, meaning that they are descended from a common evolutionary ancestor or ancestral group, especially one not shared with any other group. But the team refute this and suggest that astigmatic mites are monophyletic with plant parasitic mites and soil mites, using convincing genomic evidence. According to their estimation, the ancestral astigmatic mite branched out from soil mites about 418 million years ago possibly developed a symbiotic lifestyle and then experienced at least two rounds of evolutionary divergence.

This study also reveals the genetic fundamentals of how these mites diverged from soil mites, rapidly evolved and quickly adapted to human household environments. Professor Tsui explained that mites migrated from soil to become ectoparasitic and live on the plentiful secretions of bacteria of long-haired mammals. The bodies of short-haired mammals- human beings – are less hospitable and so the dust mite evolved and adapted to the human domestic environment; and it lives off the bacteria and fungus of dead human hair and skin flakes that fall to the ground. “The parasite becomes free living again. That is a very difficult reverse process, so we are observing a very unusual phenomenon,” he says.

Genes as perfect drug targets

The key to tracing this evolution is horizontal gene transfer (HGT), which is the movement of genetic information across mating barriers, such as DNA sharing between bacterial and animal genomes. Professor Tsui points to a path for possible intervention in mite allergy.

“In our genomic analysis of astigmatic mites, we identified many unusual HGT genes, mainly from soil bacteria. These HGTs introduced functionally important genes and enriched their adaptation novelties, especially in detoxification and digestion. Because these HGT genes have no homologue in humans, they are suggested as perfect drug targets for the pest control of astigmatic mites,” Professor Tsui adds.

The collaborative research group hopes that this pioneering comparative genomics study will expand our knowledge of astigmatic mites, provide comprehensive genomic resources for scientific researchers in this field, and ultimately contribute to the clinical diagnosis of and intervention in mite allergies.

Members of the research team also include former Postdoctoral Fellow Dr Angel Wan Tsz-yau, and Postdoctoral Fellow Dr Xiong Qing from CU Medicine’s School of Biomedical Sciences.