The lives of numerous women could be saved by a new technology to detect cervical cancer that is being developed by CUHK graduate Dr Choi Pui-wah.

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer among women globally: according to the World Health Organisation, in 2020 there were an estimated 604,000 new cases and 342,000 deaths. In Hong Kong, it is the eighth most common cancer among women, and also causes the eighth most deaths: 159 of them in 2020.

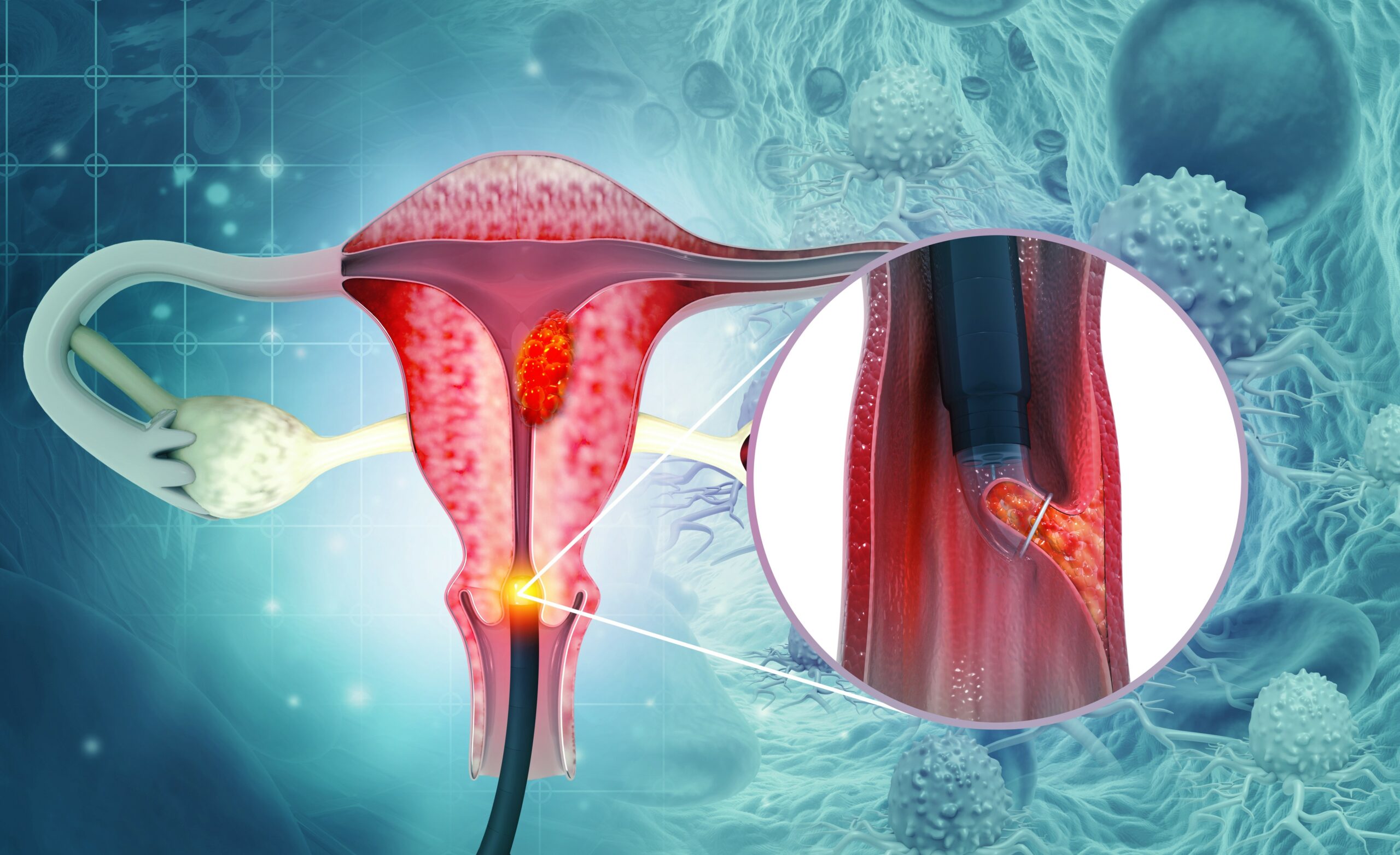

The disease can be detected through pap smears, in which a doctor or nurse uses a small scraper or brush to take a cell sample from the cervix, and then sends it to a laboratory for testing. However, for many women, this can be painful and potentially embarrassing, particularly as testing is often carried out by male medical personnel. Women often refuse regular testing for that reason, an issue that Dr Choi says is particularly acute among Asian women; in China, for example, only 25% of women have ever been tested. The accuracy of pap smears remains low, because if cells are not taken directly from the cancer-causing site, it is difficult to detect the disease. In fact, according to a 2013 study from International Journal Biomedical Science, the sensitivity of pap smears is about 51%.

That led Dr Choi, who got her bachelor’s degree in 2009 and her PhD in 2013 from CUHK’s Department of Biochemistry, to look for an alternative. She says she was inspired to do so after meeting women who had avoided getting tested and had subsequently been diagnosed with serious reproductive system diseases, leading to a far more serious surgery. As a result, she set up her company WomenX Biotech in 2019, after returning to Hong Kong in 2018 following a period undertaking research at Harvard Medical School.

Uncovering the potential of menstrual blood

“Cervical cancer is mostly caused by human papillomavirus (HPV). When menstrual blood is discharged, mutated cells may come out at the same time,” she says. “I thought: would it be more efficient to use it for testing? Biomolecules from menstrual blood have the potential to be used to assess fertility, and detect the presence of HPV. However, it is very difficult to collect and preserve the biomolecules. For example, menstrual blood dries out during transportation or processing, and microbial overgrowth will affect the accuracy of a test.”

Her answer is a technology that collects and examines menstrual blood at source, as it emerges from the body. It involves hydrogel beads roughly the size of sesame seeds, which prevent dehydration, inhibit bacteria and attract specific cancer biomarkers. A chip contains a number of hydrogel beads will be inserted underneath the fabric of sanitary napkins to collect blood. The user wears the special sanitary napkin on the day of her heaviest flow, the chip changes colour once it has absorbed enough blood, and then it can be drawn out.

At the moment, in the testing phase of the project, the chips have to be sent to a laboratory for tests. However, Dr Choi is currently developing a version for home testing, which would allow users to put the chip into a solution and drop the resulting liquid into a test kit similar to a rapid COVID-19 test. Crucially, users will be able to go through the whole process in the privacy of their own homes. Results will be ready in a few minutes, and presently record accuracy rates of between 70 and 80% are estimated.

Her team is in contact with CU Medicine’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology and other local universities regarding clinical trials of the sanitary napkin featuring a chip and a self-test kit, which is expected to launch commercially in three years’ time.

This novel technology was showcased in CUHK Entrepreneur Day 2022 and received positive response. Dr Choi believes that it will encourage women to self-screen regularly. In the future, she also hopes to apply it to the detection of other cancers such as ovarian cancer that are particularly hard to identify through conventional testing methods.