Dinosaur-to-bird transition

For the past 150 years, vertebrate palaeontologists have focused on the study of bones of dinosaurs and other prehistoric life. There are a lot of gaps to be filled in understanding prehistoric ecology, such as how dinosaurs moved, their diverse lifestyles, and how some dinosaur species including early birds developed the ability to fly. The lack of data has given rise to speculations and myths.

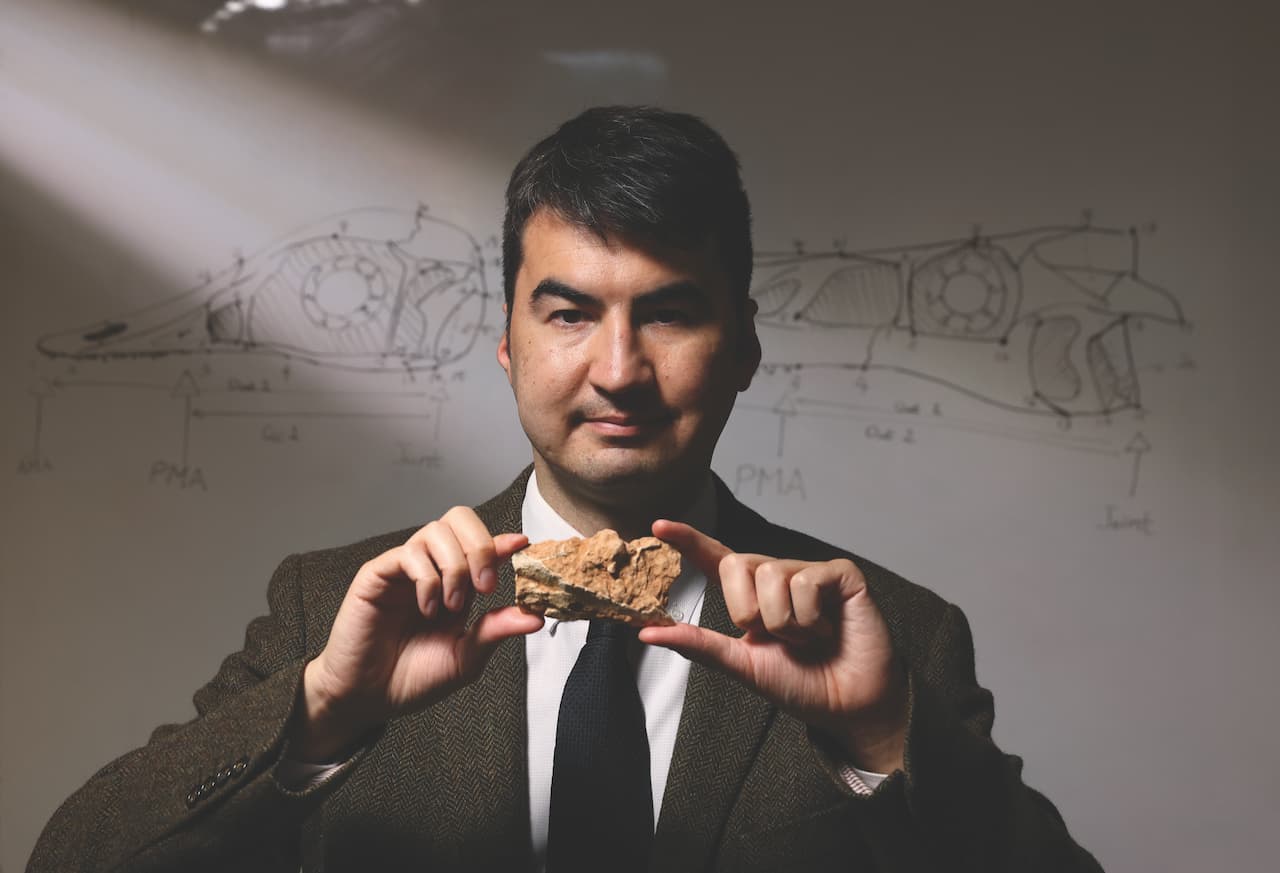

At CUHK, Professor Michael Pittman, a leading scientist in the field of vertebrate palaeontology, has been using innovative technology to revolutionise our understanding of prehistoric life. “Birds are a type of dinosaur. I am interested in how dinosaurs that could only walk and run became ones that were able to fly,” he says. “This is a key evolutionary transition, arguably the most important one since fish walked out of water. My grand challenge is to plug important gaps in our understanding of the dinosaur-to-bird transition that have puzzled scientists for years.”

New light on fossils

Professor Pittman’s team first introduced laser-stimulated fluorescence (LSF) technology in palaeontology in 2017. Before the application, ultraviolet imaging was the closest method used to study fossils.

The groundbreaking LSF technique co-developed by Professor Pittman is able to expose hidden anatomy preserved in fossils. This can outline the body and show details of the skin and other soft tissues at levels of precision that were previously impossible. In addition, LSF can show differences in the chemical composition of fossils, as the laser beam shining on a specimen interacts with the minerals that make up a fossil.

“With LSF, we have been able to put flesh back on the bones and find information that UV cannot,” he says.

Discoveries and collaborations

“Our discovery has moved the field closer to accurately reconstructing early flight capabilities.”

— Professor Michael Pittman

The CUHK team, in collaboration with experts from mainland China and United States, has discovered key information about the origin of the modern flight system of birds in a paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences last year.

“Birds today fly using muscles that are all on their chest. Using LSF, my team can now see elusive soft tissues that are rarely preserved in the fossils of early birds and validate earlier speculation that flying dinosaurs used not just muscles on the chest, but also muscles on the shoulders,” says Professor Pittman, lead author of the study. “Our discovery has moved the field closer to accurately reconstructing early flight capabilities.”

In the study, the team applied LSF to more than 1,000 fossils of early theropod flyers that lived during the Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous periods in what is now northeastern China. The specimens came from the Shandong Tianyu Museum of Nature on the mainland, with which Professor Pittman maintains a long-term working relationship.

Professor Pittman is regularly invited to study fossils in museums and universities around the world using LSF. His work featured in a special exhibition at the National Museum of Nature and Science in Tokyo this year. His LSF technique has also been applied by international researchers in the study of early birds and other animal groups, such as ammonites. His LSF work extends beyond palaeontology to archaeology.

Professor Pittman also conducts regular fieldwork in the Gobi Desert, which led to the discovery of two dinosaur species, and in the Patagonian Desert, where he investigates the Gondwanan dinosaur ecosystems.