Climate change threatens all forms of life on our planet. The urgency of the need to address this crisis is illustrated by the Climate Clock, a graphic that displays the dwindling amount of time we have left to combat climate change. Rising temperatures, increasingly frequent and intense extreme weather events, and the loss of precious biodiversity are just some of the alarming consequences that it highlights. The first two of these are increasingly reflected in the changing weather Hong Kong has been experiencing. It’s getting hotter by the year, while extreme conditions such as flooding are becoming progressively more common. The latter was brought home starkly to all of us on 7 September this year, when the rainbands of Typhoon Haikui caused 158.1mm of rain to fall in the hour between 11pm and midnight, with more than 200mm of rain in total in many areas. It was the heaviest rainfall in the city since records began in 1884, causing unprecedented flooding in urban areas – we all saw the incredible pictures of water inundating the city, from urban streets to shopping malls to Hong Kong’s metro stations. The bad news is that it’s going to get worse: by the 2040s, the highest hourly rainfall is projected to reach 230mm, an increase of more than 40% on 7 September’s extraordinary events.

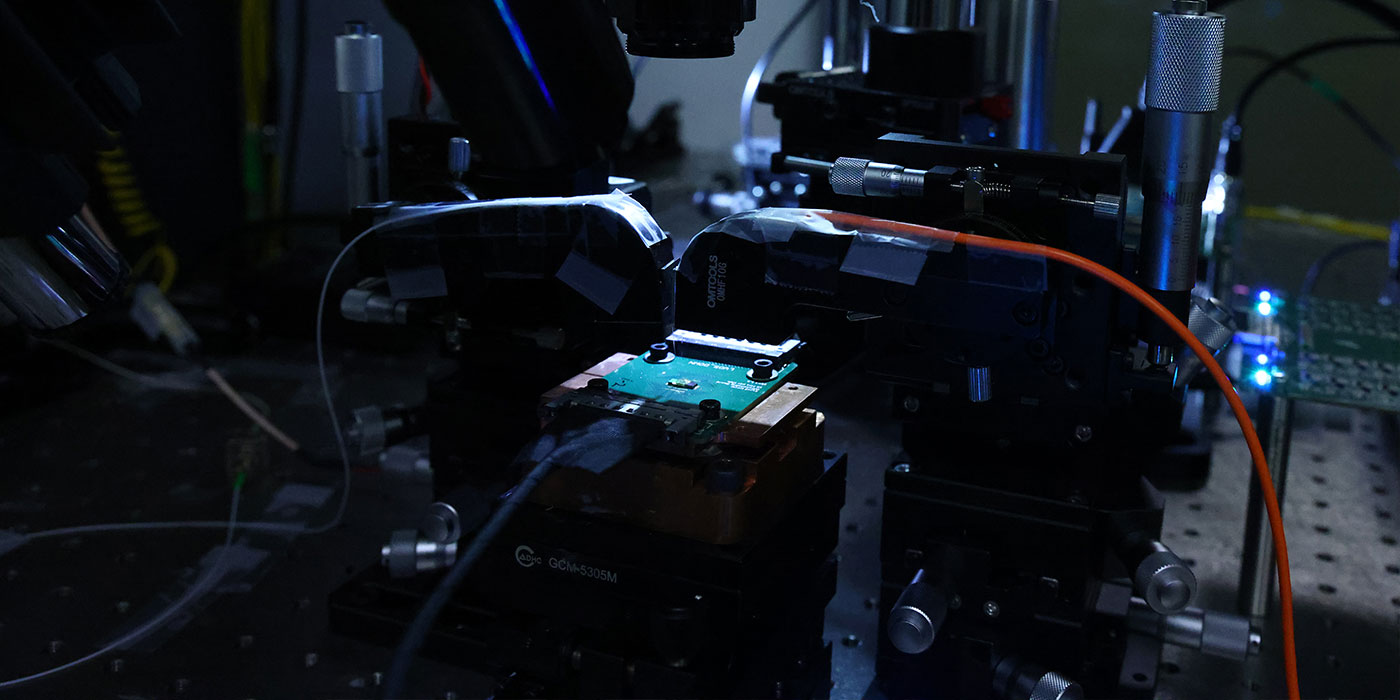

A team from CUHK’s Institute of Space and Earth Information Science is helping authorities mitigate the flooding’s worst effects. During Typhoon Haikui, it used satellite technology to monitor and analyse the floods. To do so, it deployed China’s Gaofen-3 satellite, which is equipped with Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) technology. That means that unlike traditional optical satellites, it can penetrate clouds and rain, effectively monitoring floods from space, even during extremely bad weather. The team also used the satellite’s images to measure the wind field of the typhoon, including the location of its eye, its direction and its intensity.

“These findings allowed the authorities to check the flooded areas and further evaluate the impact of flooding on residents and infrastructure,” says Institute Director Professor Kwan Mei-Po, who led the team alongside Professor Ma Peifeng.

The Institute has been engaged in research on disaster monitoring and forecasting based on remote sensing images for years. The technology is useful in assessing the impact of all sorts of adverse events.

“In addition to floods, disasters like landslides and ground subsidence can also be measured and monitored by SAR technology,” says Professor Kwan. “Our team has used multi-temporal interferometric SAR (MT-InSAR) techniques to monitor disasters such as ground subsidence in cities and landslides in mountainous areas. For example, we used it to measure and monitor the landslides in Daguan County, Zhaotong City, Yunnan Province from February 2017 to March 2019.”

Professor Kwan Mei-Po (Top row, fourth from right)

Lethal temperatures set to intensify

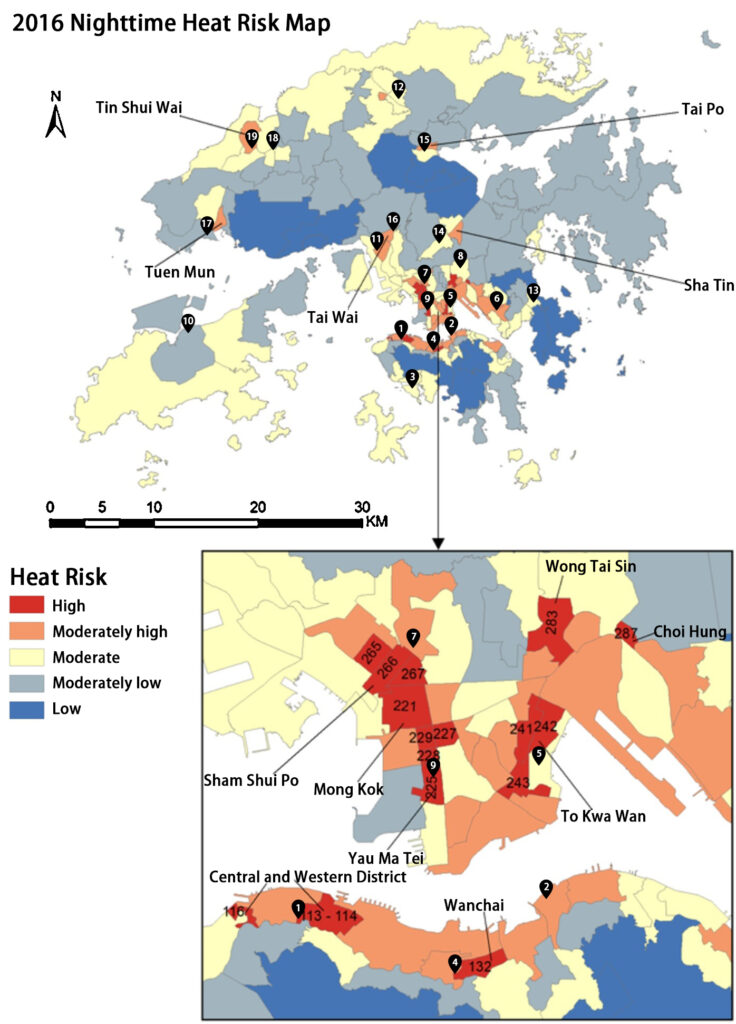

According to another study, which involved CUHK and other universities, it’s not only flooding that’s set to affect Hong Kong more and more in the future; extreme heat is set to become more common in the city – both the extremes that temperatures reach and also the length of time that extremely hot weather lasts.

Numbers from the Hong Kong Observatory indicate that there were an average of 34 very hot days and 36 hot nights a year between 2012 and 2021, defined as the temperature not falling below 33 and 28 degrees respectively. Thanks to a combination of climate change and increased urbanisation, the number of hot nights is expected to increase by 50% in the 2040s – and if greenhouse gas emissions don’t change, those numbers will soar to about 126 and 136 by late this century.

There are government-run temporary night heat shelters that open at night when it’s extremely hot. However, their locations are not widely known and not particularly convenient for a lot of people, particularly those of advanced years of with mobility issues; and they’re not very appealing places to go. That means there’s an urgent need for more of them, along with improvements that will drive uptake.

“We recommend that the government expands the network of cooling spots to areas with the highest heat risks as a top priority,” says Edward Ng, Yao Ling-Sun Professor of Architecture, the principal coordinator of the research. “It is important to ensure that temporary heat shelters are situated in easily accessible locations, including ones that can be reached by senior citizens with limited mobility. Moreover, there should be efforts to enhance the environment, facilities and management of these heat shelters to make them inviting for people to rest and seek respite whenever necessary.”

The design of parks and other public spaces needs to be improved so they provide more cool spots, he adds – in particular, shaded areas and features such as fountains, wet play areas and misting sprays that help to reduce the temperature. Meanwhile, we all have a role to play in trying to prevent the worst-case scenario from happening.

“Individuals should also be prepared for extreme weather conditions by enhancing disaster preparedness and ensuring they have readily available emergency survival kits. Reducing carbon emissions is an urgent necessity that requires collective action from both individuals and businesses.”