While nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is a vanishingly rare form of cancer among most populations worldwide, that’s emphatically not true in Hong Kong. The disease disproportionately affects certain southern Chinese groups, mainly those from Guangdong, Guangxi and Hainan, giving rise to its nickname: Cantonese cancer. It’s the ninth most common cancer among men in Hong Kong, but it’s the commonest of all here among men aged 20 to 44. That reflects the fact that it affects men more than women at a rate of about 2.6 to 1, and it tends to strike early: the commonest age of onset is the 30s and 40s.

Its location in the nasopharynx, the area at the back of the nasal cavity, buried deep inside the head, means it can be hard to detect. Moreover, it can often be asymptomatic during early stages, plus many of the symptoms that do manifest can easily be mistaken for less serious conditions: a blocked ear, hearing loss and tinnitus; fever; nasal obstruction; nosebleeds; and headaches (the real giveaways are a lump in the neck caused by a swollen lymph node, and blood in the saliva and in discharge from the nose). As a result, NPC patients often present at a relatively late stage. Unfortunately, prognosis worsens rapidly as the disease progresses: a five year survival rate of 90% at early stages drops to below 50% later.

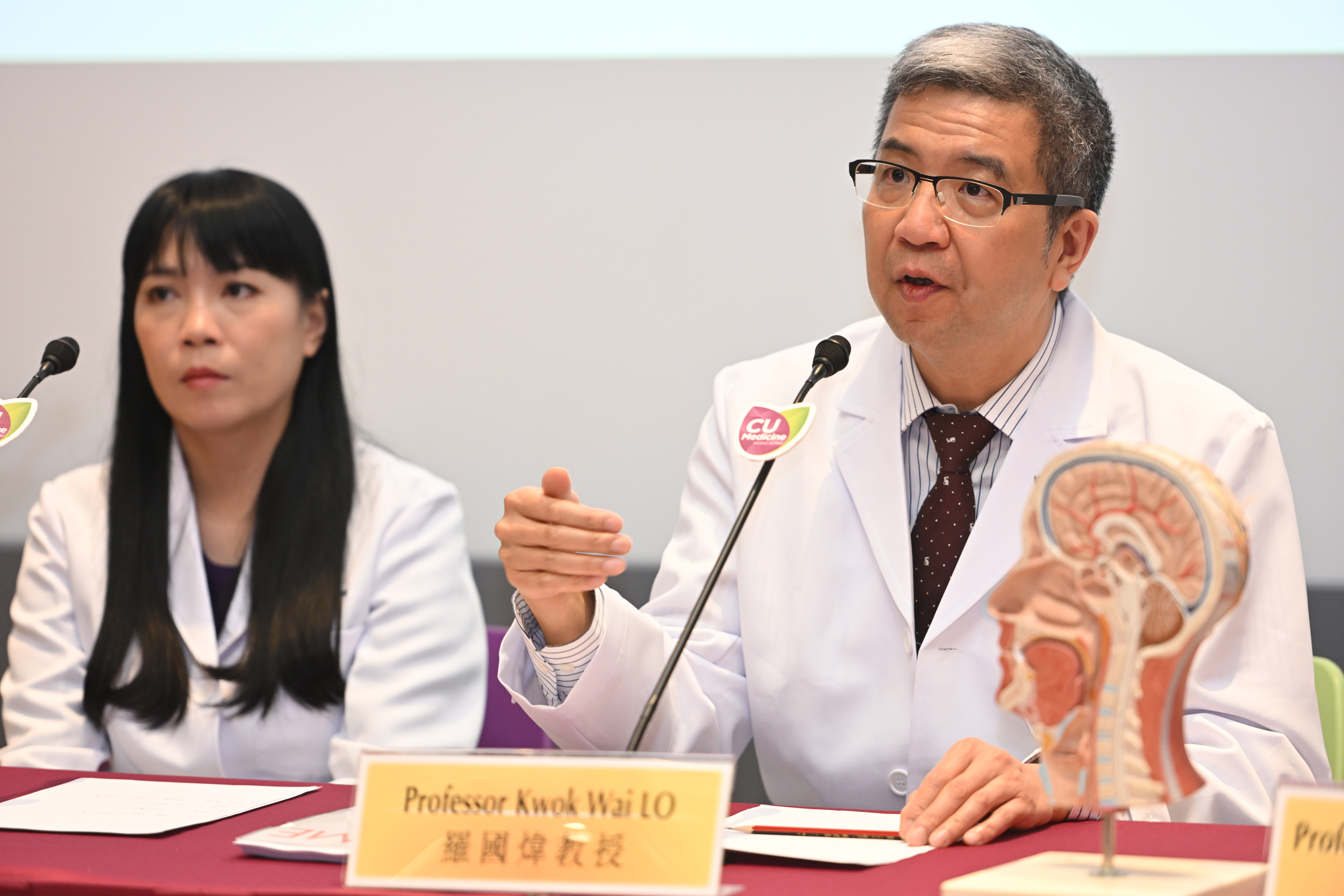

Its location also makes it challenging to treat. “NPCs are always located near many critical structures in the patient’s head and neck region; surgical operations are only used in some local recurrence cases,” says Professor Lo Kwok-wai, Professor in the Department of Anatomical and Cellular Pathology at CU Medicine.

Instead, radiotherapy combined with chemotherapy tends to be the first line of treatment; chemotherapy is also combined with immunotherapy for patients with recurrent and metastatic tumours.

While other factors are also at play, such as genetics and possibly diet, NPC is strongly associated with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), a member of the herpes family that is widely present in humans, and that is also linked with a wide range of other medical conditions, including other cancers such as Hodgkin’s lymphoma and gastric cancer.

This association means that the virus is a target for treatment of the disease. Professor Lo and a CU Medicine team have developed an mRNA drug – technically a lipid nanoparticle encapsulating nucleoside-modified mRNA, which encodes an artificial transcriptional activator named mTZ3-LNP – that has been tested on mice and shown to reduce tumour growth. (In fact, the components of the lipid nanoparticle are famous – they were previously used in the Covid mRNA vaccine.)

The drug exploits the fact that EBV remains latent within the cells of the body. It acts like a kill switch, inducing the virus to enter what’s called its lytic cycle, which causes its host cell to die – and meaning that it effectively commits suicide. The drug is delivered to both normal and tumour cells by intravenous injection, but only binds to and activates the EBV lytic genes, with no effect on any of the other, healthy cells.

“EBV infection is a driver event during NPC development and essential for maintenance of the tumour cells,” says Professor Lo. “While almost all NPC is EBV-positive, the EBV genome is present in each of the NPC tumour cells, but not in the normal cells of the body, except few specific blood cells. Thus, EBV-targeting treatments such as the mRNA drug that induces the lytic reactivation to kill the EBV-positive cells” are effective against the condition. “The concept of targeting EBV-positive cancer via reactivation of the viral lytic cycle has been around for more than two decades. The lack of efficient drugs or small molecules to induce EBV lytic genes and the broad spectrum of cytotoxicity [potential to cause cell damage] of the identified chemical lytic inducers have hampered its clinical application.”

The genesis of the current project is a trip Professor Lo made to CUHK’s partner in the project, The Jackson Laboratory in the US, in 2017, when he discussed using gene editing tools to activate EBV lytic genes. A lengthy screening process identified mTZ3-LNP as a candidate to do so.

mRNA drugs have already been used to treat other types of cancer, such as of the liver. Professor Lo says the new drug could potentially also be used to treat other cancers associated with EBV.

“In our preclinical mouse models, we demonstrated that the mRNA drug treatment significantly inhibited tumour growth and killed the cancer cells of all NPC and gastric cancer examined. No body weight loss and other side effects were detected in the mice after long term treatment; unlike chemotherapy, the mRNA drug is not toxic and does not alter any cellular activities of the EBV-negative cells.”

The next stage, he says, is to test the drug in concert with targeted immunotherapy – with the potential that working together, they could provide even more effective treatment.