Hong Kong can be a challenging place to live, with its fast pace of the life and the constant pressure to get ahead. Unsurprisingly, rates of depression are high in the city, running to 8% or more[1]. Meanwhile globally, about 280 million people suffer from the condition[2]. It’s a disease that can cause untold misery, affecting every aspect of their lives and those of the people around them.

The best way to diagnose depression is for patients to see a psychiatrist. However, in common with many other places, Hong Kong has a shortage of those. Also, a lot of sufferers are reluctant to speak up, fearing the social stigma sometimes attached to conditions like depression. As a result, more than 70% of people[3] in Hong Kong with common mental health disorders such as depression don’t even seek help.

So there’s an urgent need for ways to spread the burden and make it easier to diagnose depression, beyond traditional, face-to-face clinical evaluations. Two new technological tools developed by The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) researchers promise to do exactly that.

Show and tell: app finds clues in users’ videos

The power of combining several digital tools together to detect depression was shown by a recent study from CUHK’s Faculty of Medicine (CU Medicine). Deploying the power of AI, the research team developed an app that measures and analyses users’ facial expression, voice, language and subjective mood state, as well as rest-activity statistics, as a way of detecting depression early.

They tested it in a case-control study, putting together a multidisciplinary team of professionals including psychiatrists, psychologists, software engineers and data/AI scientists. The participants, including patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) and a control group free from psychiatric disorders, wore an actigraph, which monitored their physical activity. They also recorded their mental state using the app, in the form of video clips four times a day, in which they were asked to talk about their mood at the time and their activities during the previous four hours. Finally, an artificial neural network (ANN), a machine learning model, used all that information to build a model that could predict depression.

The technology found that, compared to the control group, depressive patients moved less, had less regular circadian rhythms, narrowed their eyebrows more, pulled the corners of their lips less, referred to themselves more, used more negative emotion words, spoke less, had larger variations in the duration of pauses during speech and reported lower average happiness levels.

“Depression is more than simply sadness but encompasses a series of physiological, cognitive, mood and rest-activity changes; therefore, we used one week of real-life multimodal measurement to assess depression in Hong Kong Chinese people,” says Professor Wing Yun-kwok, Choh-Ming Li Professor of Psychiatry and Chairman at CU Medicine’s Department of Psychiatry.

“The main strength of our digital diagnostic system is that it is based on convenient, feasible, remote measurements, without clinicians being involved. Moreover, the clinical outcome is assessed by trained medical researchers rather than simply based on self-reporting questionnaires. Our app users showed a satisfactory rate of adherence, suggesting that the study works well and could be applied to more subjects.”

Though the app is not accessible to the public yet, the team believes that this handy tool holds the promise of making a real clinical impact. In addition to offering easier mental health assessments, it can also provide additional information related to patients’ symptoms without recall bias, as well as increasing awareness of depression, and could even be used to train medical students.

The researchers plan to expand the research to a bigger range of ages and disorders in future, including more subtypes of depression, and hope to develop a fully automated system that can provide real-time feedback.

“We are recruiting more MDD patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) who have not previously taken antidepressant medications. The purpose is to evaluate whether our app can detect changes in MDD symptoms over time in patients who have been newly prescribed antidepressant treatment,” says Professor Wing.

Windows on the soul: reading eyes to detect depression

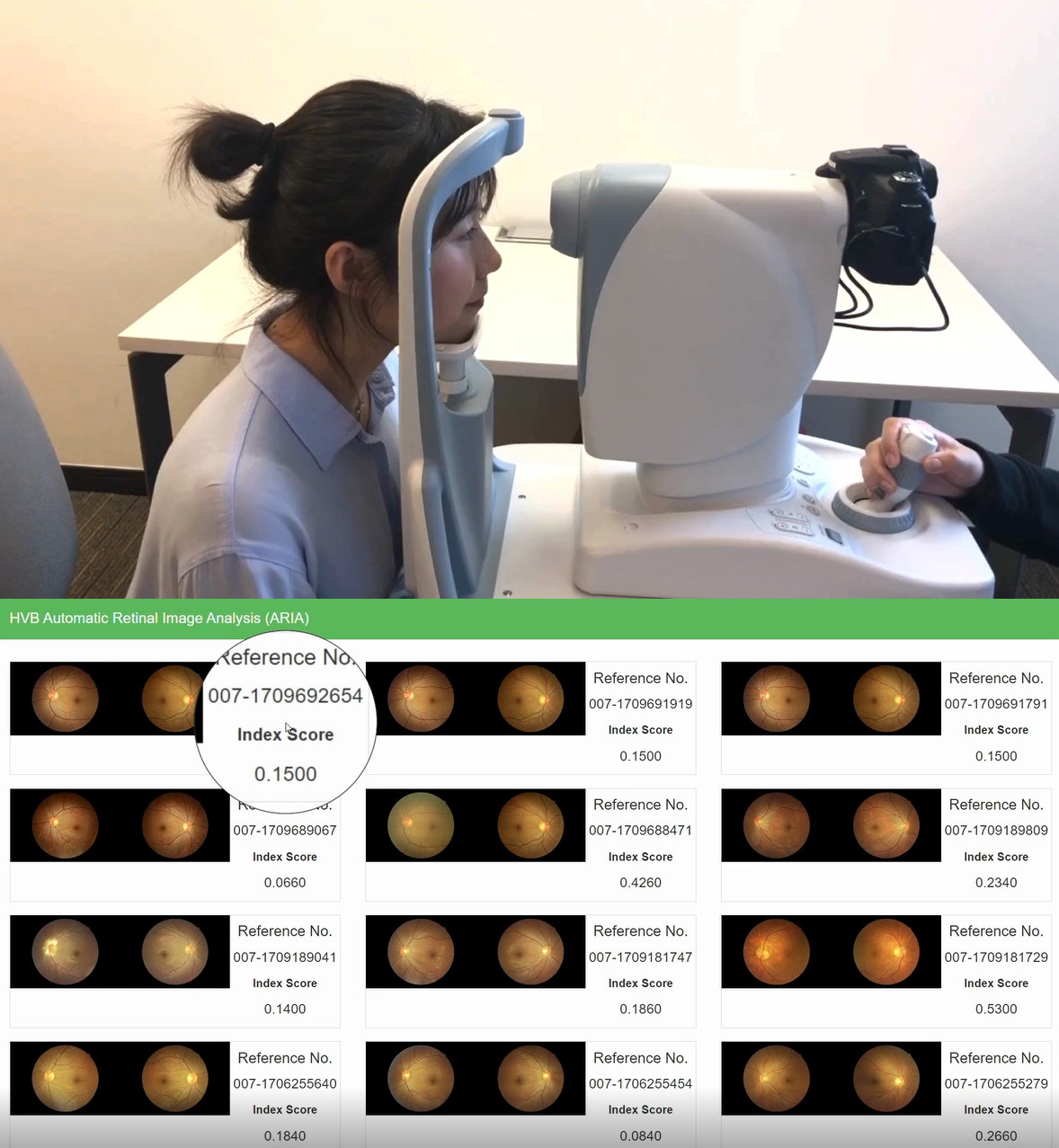

Looking at images of people’s retinas can also help assess depression accurately – as a team from CU Medicine’s Centre for Clinical Research and Biostatistics (CCRB) has demonstrated. They showed that AI-based Automatic Retinal Image Analysis (ARIA) technology developed by CUHK – already known to be useful in detecting different types of health disease risks – can also help to detect whether adults are at risk of depression.

The detection is as simple as a normal eye checkup: just let the machine take pictures of both eyes, and the fundus images will be uploaded to the cloud database. AI will analyse and compare the photos to those of patients and non-patients, and evaluate whether specific characteristics related to depression are shown. Results can be known within minutes.

The team first tested ARIA’s ability to detect depression, anxiety and stress in patients who have recovered from nasopharyngeal cancer, finding it could do so with 98.2% sensitivity and 91.7% specificity. The team then extended the study to psychiatric hospitals and obtained similar results, further confirming that ARIA can detect patients with depression.

“A fast, objective, efficient screening test for depression is urgently needed,” says Professor Benny Zee Chung-ying, developer of ARIA and Director of CCRB at The Jockey Club School of Public Health and Primary Care at CU Medicine. “ARIA is non-invasive, fast and simple to use in the community. It only requires retinal images to be taken, without the need to ask many questions. We can do population screening or screening of particular groups to identify high-risk subjects for early prevention. In addition, retinal image analysis is objective, instead of relying on subjects’ responses.”

Professor Zee explains that there are several ways that information can be used: “For the general population, we want to increase their self-awareness. Once we detect high-risk subjects using ARIA, we suggest lifestyle interventions such as physical activities, a Mediterranean diet, reducing smoking and alcohol consumption, improving sleep quality, increasing social connection with hobby groups and so on. For the depressive population, we want to monitor depression using ARIA while patients are in treatment and encourage lifestyle interventions to prolong the duration of remission.”

The innovation recently won a gold medal at the International Exhibition of Inventions Geneva. The team plan to launch the system publicly by the end of 2024, working with organisations such as healthcare providers, NGOs and insurance companies. They’re also working on adapting it to detect other psychological conditions.

[1] According to the 2015 Hong Kong Mental Morbidity Survey. (Lam, L. C. W., Wong, C. S. M., Wang, M. J., Chan, W. C., Chen, E. Y. H., Ng, R. M. K., … & Bebbington, P. (2015). Prevalence, psychosocial correlates and service utilization of depressive and anxiety disorders in Hong Kong: the Hong Kong Mental Morbidity Survey (HKMMS). Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 50, 1379-1388.)

[2] According to the World Health Organization (https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression).

[3] According to the 2015 Hong Kong Mental Morbidity Survey. (Lam, L. C. W., Wong, C. S. M., Wang, M. J., Chan, W. C., Chen, E. Y. H., Ng, R. M. K., … & Bebbington, P. (2015). Prevalence, psychosocial correlates and service utilization of depressive and anxiety disorders in Hong Kong: the Hong Kong Mental Morbidity Survey (HKMMS). Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 50, 1379-1388.)