English

繁體中文

简体中文

It’s not often that a new species of abelisaurid dinosaur gets discovered – the habitat of the famous Carnotaurus hasn’t yielded another abelisaurid since it was found 40 years ago – but that’s exactly what a CUHK-led team has just done. The extensive set of bones they found in South America come from Koleken inakayali, an agile apex predator that inhabited the ancient southern supercontinent of Gondwana 60-plus million years ago. The discovery sheds light on how predatory dinosaurs evolved and shows that more than one top predator lived side by side in Late Cretaceous ecosystems.

It’s not often that a new species of abelisaurid dinosaur gets discovered – the habitat of the famous Carnotaurus hasn’t yielded another abelisaurid since it was found 40 years ago – but that’s exactly what a CUHK-led team has just done. The extensive set of bones they found in South America come from Koleken inakayali, an agile apex predator that inhabited the ancient southern supercontinent of Gondwana 60-plus million years ago. The discovery sheds light on how predatory dinosaurs evolved and shows that more than one top predator lived side by side in Late Cretaceous ecosystems.

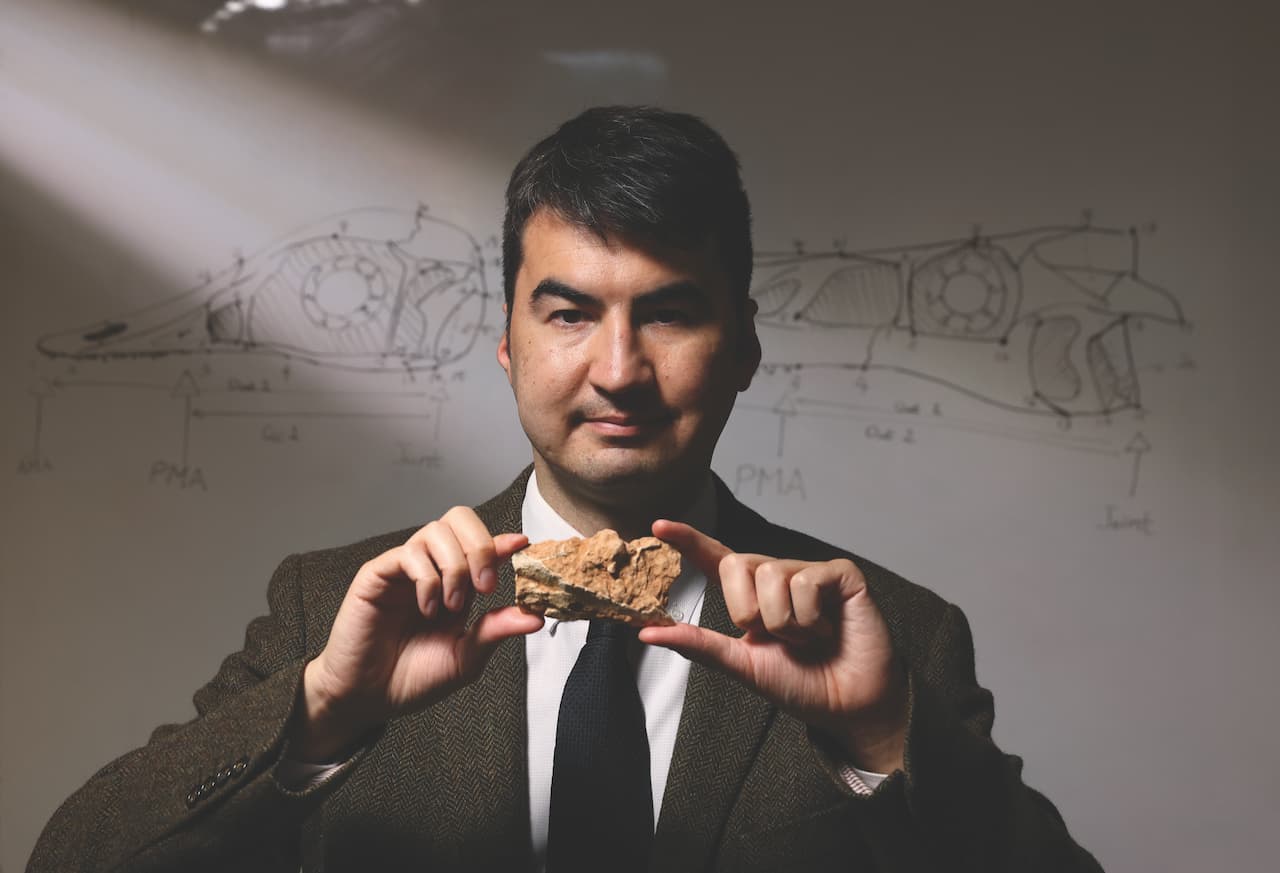

For the past 150 years, vertebrate palaeontologists have focused on the study of bones of dinosaurs and other prehistoric life. There are a lot of gaps to be filled in understanding prehistoric ecology, and the lack of data has given rise to speculations and myths. At CUHK, Professor Michael Pittman, a leading scientist in the field of vertebrate palaeontology, has been using innovative technology to revolutionise our understanding of pre-historic life.

A CUHK palaeobiologist co-developed laser stimulated fluorescence imaging while pursuing how running dinosaurs evolved into flying birds. The technique revealed unseen fossilised tissues so well, it inspired a crossover to a completely different discipline, archaeology.